Chapter 8 Communication of results

For this chapter, load the following packages:

library(tidyverse)

library(survey)

library(srvyr)

library(srvyrexploR)

library(gt)

library(gtsummary)We are using data from ANES as described in Chapter 4. As a reminder, here is the code to create the design objects for each to use throughout this chapter. For ANES, we need to adjust the weight so it sums to the population instead of the sample (see the ANES documentation and Chapter 4 for more information).

8.1 Introduction

After finishing the analysis and modeling, we proceed to the task of communicating the survey results. Our audience may range from seasoned researchers familiar with our survey data to newcomers encountering the information for the first time. We should aim to explain the methodology and analysis while presenting findings in an accessible way, and it is our responsibility to report information with care.

Before beginning any dissemination of results, consider questions such as:

- How are we presenting results? Examples include a website, print, or other media. Based on the medium, we might limit or enhance the use of graphical representation.

- What is the audience’s familiarity with the study and/or data? Audiences can range from the general public to data experts. If we anticipate limited knowledge about the study, we should provide detailed descriptions (we discuss recommendations later in the chapter).

- What are we trying to communicate? It could be summary statistics, trends, patterns, or other insights. Tables may suit summary statistics, while plots are better at conveying trends and patterns.

- Is the audience accustomed to interpreting plots? If not, include explanatory text to guide them on how to interpret the plots effectively.

- What is the audience’s statistical knowledge? If the audience does not have a strong statistics background, provide text on standard errors, confidence intervals, and other estimate types to enhance understanding.

8.2 Describing results through text

As analysts, we often emphasize the data, and communicating results can sometimes be overlooked. To be effective communicators, we need to identify the appropriate information to share with our audience. Chapters 2 and 3 provide insights into factors we need to consider during analysis, and they remain relevant when presenting results to others.

8.2.1 Methodology

If we are using existing data, methodologically sound surveys provide documentation about how the survey was fielded, the questionnaires, and other necessary information for analyses. For example, the survey’s methodology reports should include the population of interest, sampling procedures, response rates, questionnaire documentation, weighting, and a general overview of disclosure statements. Many American organizations follow the American Association for Public Opinion Research’s (AAPOR) Transparency Initiative. The AAPOR Transparency Initiative requires organizations to include specific details in their methodology, making it clear how we can and should analyze and interpret the results. Being transparent about these methods is vital for the scientific rigor of the field.

The details provided in Chapter 2 about the survey process should be shared with the audience when presenting the results. When using publicly available data, like the examples in this book, we can often link to the methodology report in our final output. We should also provide high-level information for the audience to quickly grasp the context around the findings. For example, we can mention when and where the study was conducted, the population’s age range, or other contextual details. This information helps the audience understand how generalizable the results are.

Providing this material is especially important when no methodology report is available for the analyzed data. For example, if we conducted a new survey for a specific purpose, we should document and present all the pertinent information during the analysis and reporting process. Adhering to the AAPOR Transparency Initiative guidelines is a reliable method to guarantee that all essential information is communicated to the audience.

8.2.2 Analysis

Along with the survey methodology and weight calculations, we should also share our approach to preparing, cleaning, and analyzing the data. For example, in Chapter 6, we compared education distributions from the ANES survey to the American Community Survey (ACS). To make the comparison, we had to collapse the education categories provided in the ANES data to match the ACS. The process for this particular example may seem straightforward (like combining bachelor’s and graduate degrees into a single category), but there are multiple ways to deal with the data. Our choice is just one of many. We should document both the original ANES question and response options and the steps we took to match them with ACS data. This transparency helps clarify our analysis to our audience.

Missing data is another instance where we want to be unambiguous and upfront with our audience. In this book, numerous examples and exercises remove missing data, as this is often the easiest way to handle them. However, there are circumstances where missing data holds substantive importance, and excluding them could introduce bias (see Chapter 11). Being transparent about our handling of missing data is important to maintaining the integrity of our analysis and ensuring a comprehensive understanding of the results.

8.2.3 Results

While tables and graphs are commonly used to communicate results, there are instances where text can be more effective in sharing information. Narrative details, such as context around point estimates or model coefficients, can go a long way in improving our communication. We have several strategies to effectively convey the significance of the data to the audience through text.

First, we can highlight important data elements in a sentence using plain language. For example, if we were looking at election polling data conducted before an election, we could say:

As of [DATE], an estimated XX% of registered U.S. voters say they will vote for [CANDIDATE NAME] for president in the [YEAR] general election.

This sentence provides key pieces of information in a straightforward way:

- [DATE]: Given that polling data are time-specific, providing the date of reference lets the audience know when these data were valid.

- Registered U.S. voters: This tells the audience who we surveyed, letting them know the population of interest.

- XX%: This part provides the estimated percentage of people voting for a specific candidate for a specific office.

- [YEAR] general election: Adding this gives more context about the election type and year. The estimate would take on a different meaning if we changed it to a primary election instead of a general election.

We also included the word “estimated.” When presenting aggregate survey results, we have errors around each estimate. We want to convey this uncertainty rather than talk in absolutes. Words like “estimated,” “on average,” or “around” can help communicate this uncertainty to the audience. Instead of saying “XX%,” we can also say “XX% (+/- Y%)” to show the margin of error. Confidence intervals can also be incorporated into the text to assist readers.

Second, providing context and discussing the meaning behind a point estimate can help the audience glean some insight into why the data are important. For example, when comparing two values, it can be helpful to highlight if there are statistically significant differences and explain the impact and relevance of this information. This is where we should do our best to be mindful of biases and present the facts logically.

Keep in mind how we discuss these findings can greatly influence how the audience interprets them. If we include speculation, phrases like “the authors speculate” or “these findings may indicate,” it relays the uncertainty around the notion while still lending a plausible solution. Additionally, we can present alternative viewpoints or competing discussion points to explain the uncertainty in the results.

8.3 Visualizing data

Although discussing key findings in the text is important, presenting large amounts of data in tables or visualizations is often more digestible for the audience. Effectively combining text, tables, and graphs can be powerful in communicating results. This section provides examples of using the {gt}, {gtsummary}, and {ggplot2} packages to enhance the dissemination of results (Iannone et al. 2025; Sjoberg et al. 2021; Wickham 2016).

8.3.1 Tables

Tables are a great way to provide a large amount of data when individual data points need to be examined. However, it is important to present tables in a reader-friendly format. Numbers should align, rows and columns should be easy to follow, and the table size should not compromise readability. Using key visualization techniques, we can create tables that are informative and nice to look at. Many packages create easy-to-read tables (e.g., {kable} + {kableExtra}, {gt}, {gtsummary}, {DT}, {formattable}, {flextable}, {reactable}). We appreciate the flexibility, ability to use pipes (e.g., %>%), and numerous extensions of the {gt} package. While we focus on {gt} here, we encourage learning about others, as they may have additional helpful features. Please note, at this time, {gtsummary} needs additional features to be widely used for survey analysis, particularly due to its lack of ability to work with replicate designs. We provide one example using {gtsummary} and hope it evolves into a more comprehensive tool over time.

Transitioning {srvyr} output to a {gt} table

Let’s start by using some of the data we calculated earlier in this book. In Chapter 6, we looked at data on trust in government with the proportions calculated below:

trust_gov <- anes_des %>%

drop_na(TrustGovernment) %>%

group_by(TrustGovernment) %>%

summarize(trust_gov_p = survey_prop())

trust_gov## # A tibble: 5 × 3

## TrustGovernment trust_gov_p trust_gov_p_se

## <fct> <dbl> <dbl>

## 1 Always 0.0155 0.00204

## 2 Most of the time 0.132 0.00553

## 3 About half the time 0.309 0.00829

## 4 Some of the time 0.434 0.00855

## 5 Never 0.110 0.00566

The default output generated by R may work for initial viewing inside our IDE or when creating basic output in an R Markdown or Quarto document. However, when presenting these results in other publications, such as the print version of this book or with other formal dissemination modes, modifying the display can improve our reader’s experience.

Looking at the output from trust_gov, a couple of improvements stand out: (1) switching to percentages instead of proportions and (2) removing the variable names as column headers. The {gt} package is a good tool for implementing better labeling and creating publishable tables. Let’s walk through some code as we make a few changes to improve the table’s usefulness.

First, we initiate the formatted table with the gt() function on the trust_gov tibble previously created. Next, we use the argument rowname_col() to designate the TrustGovernment column as the label for each row (called the table “stub”). We apply the cols_label() function to create informative column labels instead of variable names and then the tab_spanner() function to add a label across multiple columns. In this case, we label all columns except the stub with “Trust in Government, 2020.” We then format the proportions into percentages with the fmt_percent() function and reduce the number of decimals shown to one with decimals = 1. Finally, the tab_caption() function adds a table title for the HTML version of the book. We can use the caption for cross-referencing in R Markdown, Quarto, and bookdown, as well as adding it to the list of tables in the book. These changes are all seen in Table 8.1.

trust_gov_gt <- trust_gov %>%

gt(rowname_col = "TrustGovernment") %>%

cols_label(

trust_gov_p = "%",

trust_gov_p_se = "s.e. (%)"

) %>%

tab_spanner(

label = "Trust in Government, 2020",

columns = c(trust_gov_p, trust_gov_p_se)

) %>%

fmt_percent(decimals = 1)| Trust in Government, 2020 | ||

|---|---|---|

| % | s.e. (%) | |

| Always | 1.6% | 0.2% |

| Most of the time | 13.2% | 0.6% |

| About half the time | 30.9% | 0.8% |

| Some of the time | 43.4% | 0.9% |

| Never | 11.0% | 0.6% |

We can add a few more enhancements, such as a title (which is different from a caption27), a data source note, and a footnote with the question information, using the functions tab_header(), tab_source_note(), and tab_footnote(). If having the percentage sign in both the header and the cells seems redundant, we can opt for fmt_number() instead of fmt_percent() and scale the number by 100 with scale_by = 100. The resulting table is displayed in Table 8.2.

trust_gov_gt2 <- trust_gov_gt %>%

tab_header("American voter's trust

in the federal government, 2020") %>%

tab_source_note(

md("*Source*: American National Election Studies, 2020")

) %>%

tab_footnote(

"Question text: How often can you trust the federal government

in Washington to do what is right?"

) %>%

fmt_number(

scale_by = 100,

decimals = 1

)| American voter's trust in the federal government, 2020 | ||

| Trust in Government, 2020 | ||

|---|---|---|

| % | s.e. (%) | |

| Always | 1.6 | 0.2 |

| Most of the time | 13.2 | 0.6 |

| About half the time | 30.9 | 0.8 |

| Some of the time | 43.4 | 0.9 |

| Never | 11.0 | 0.6 |

| Source: American National Election Studies, 2020 | ||

| Question text: How often can you trust the federal government in Washington to do what is right? | ||

Expanding tables using {gtsummary}

The {gtsummary} package simultaneously summarizes data and creates publication-ready tables. Initially designed for clinical trial data, it has been extended to include survey analysis in certain capacities. At this time, it is only compatible with survey objects using Taylor’s Series Linearization and not replicate methods. While it offers a restricted set of summary statistics, the following are available for categorical variables:

{n}frequency{N}denominator, or respondent population{p}proportion (stylized as a percentage by default){p.std.error}standard error of the sample proportion{deff}design effect of the sample proportion{n_unweighted}unweighted frequency{N_unweighted}unweighted denominator{p_unweighted}unweighted formatted proportion (stylized as a percentage by default)

The following summary statistics are available for continuous variables:

{median}median{mean}mean{mean.std.error}standard error of the sample mean{deff}design effect of the sample mean{sd}standard deviation{var}variance{min}minimum{max}maximum{p#}any integer percentile, where#is an integer from 0 to 100{sum}sum

In the following example, we build a table using {gtsummary}, similar to the table in the {gt} example. The main function we use is tbl_svysummary(). In this function, we include the variables we want to analyze in the include argument and define the statistics we want to display in the statistic argument. To specify the statistics, we apply the syntax from the {glue} package, where we enclose the variables we want to insert within curly brackets. We must specify the desired statistics using the names listed above. For example, to specify that we want the proportion followed by the standard error of the proportion in parentheses, we use {p} ({p.std.error}). Table 8.3 displays the resulting table.

anes_des_gtsum <- anes_des %>%

tbl_svysummary(

include = TrustGovernment,

statistic = list(all_categorical() ~ "{p} ({p.std.error})")

)| Characteristic | N = 231,034,1251 |

|---|---|

| PRE: How often trust government in Washington to do what is right [revised] | |

| Always | 1.6 (0.00) |

| Most of the time | 13 (0.01) |

| About half the time | 31 (0.01) |

| Some of the time | 43 (0.01) |

| Never | 11 (0.01) |

| Unknown | 673,773 |

| 1 % (SE(%)) | |

The default table (shown in Table 8.3) includes the weighted number of missing (or Unknown) records. The standard error is reported as a proportion, while the proportion is styled as a percentage. In the next step, we remove the Unknown category by setting the missing argument to “no” and format the standard error as a percentage using the digits argument. To improve the table for publication, we provide a more polished label for the “TrustGovernment” variable using the label argument. The resulting table is displayed in Table 8.4.

anes_des_gtsum2 <- anes_des %>%

tbl_svysummary(

include = TrustGovernment,

statistic = list(all_categorical() ~ "{p} ({p.std.error})"),

missing = "no",

digits = list(TrustGovernment ~ style_percent),

label = list(TrustGovernment ~ "Trust in Government, 2020")

)| Characteristic | N = 231,034,1251 |

|---|---|

| Trust in Government, 2020 | |

| Always | 1.6 (0.2) |

| Most of the time | 13 (0.6) |

| About half the time | 31 (0.8) |

| Some of the time | 43 (0.9) |

| Never | 11 (0.6) |

| 1 % (SE(%)) | |

Table 8.4 is closer to our ideal output, but we still want to make a few changes. To exclude the term “Characteristic” and the estimated population size (N), we can modify the header using the modify_header() function to update the label. Further adjustments can be made based on personal preferences, organizational guidelines, or other style guides. If we prefer having the standard error in the header, similar to the {gt} table, instead of in the footnote (the {gtsummary} default), we can make these changes by specifying stat_0 in the modify_header() function. Additionally, using modify_footnote() with update = everything() ~ NA removes the standard error from the footnote. After transforming the object into a {gt} table using as_gt(), we can add footnotes and a title using the same methods explained in the previous section. This updated table is displayed in Table 8.5.

anes_des_gtsum3 <- anes_des %>%

tbl_svysummary(

include = TrustGovernment,

statistic = list(all_categorical() ~ "{p} ({p.std.error})"),

missing = "no",

digits = list(TrustGovernment ~ style_percent),

label = list(TrustGovernment ~ "Trust in Government, 2020")

) %>%

modify_footnote(update = everything() ~ NA) %>%

modify_header(

label = " ",

stat_0 = "% (s.e.)"

) %>%

as_gt() %>%

tab_header("American voter's trust

in the federal government, 2020") %>%

tab_source_note(

md("*Source*: American National Election Studies, 2020")

) %>%

tab_footnote(

"Question text: How often can you trust the federal government

in Washington to do what is right?"

)| American voter's trust in the federal government, 2020 | |

| % (s.e.) | |

|---|---|

| Trust in Government, 2020 | |

| Always | 1.6 (0.2) |

| Most of the time | 13 (0.6) |

| About half the time | 31 (0.8) |

| Some of the time | 43 (0.9) |

| Never | 11 (0.6) |

| Source: American National Election Studies, 2020 | |

| Question text: How often can you trust the federal government in Washington to do what is right? | |

We can also include summaries of more than one variable in the table. These variables can be either categorical or continuous. In the following code and Table 8.6, we add the mean age by updating the include, statistic, and digits arguments.

anes_des_gtsum4 <- anes_des %>%

tbl_svysummary(

include = c(TrustGovernment, Age),

statistic = list(

all_categorical() ~ "{p} ({p.std.error})",

all_continuous() ~ "{mean} ({mean.std.error})"

),

missing = "no",

digits = list(TrustGovernment ~ style_percent,

Age ~ c(1, 2)),

label = list(TrustGovernment ~ "Trust in Government, 2020")

) %>%

modify_footnote(update = everything() ~ NA) %>%

modify_header(label = " ",

stat_0 = "% (s.e.)") %>%

as_gt() %>%

tab_header(

"American voter's trust in the federal government, 2020") %>%

tab_source_note(

md("*Source*: American National Election Studies, 2020")

) %>%

tab_footnote(

"Question text: How often can you trust the federal government

in Washington to do what is right?"

) %>%

tab_caption("Example of {gtsummary} table with trust in government

estimates and average age")| American voter's trust in the federal government, 2020 | |

| % (s.e.) | |

|---|---|

| Trust in Government, 2020 | |

| Always | 1.6 (0.2) |

| Most of the time | 13 (0.6) |

| About half the time | 31 (0.8) |

| Some of the time | 43 (0.9) |

| Never | 11 (0.6) |

| PRE: SUMMARY: Respondent age | 47.3 (0.36) |

| Source: American National Election Studies, 2020 | |

| Question text: How often can you trust the federal government in Washington to do what is right? | |

With {gtsummary}, we can also calculate statistics by different groups. Let’s modify the previous example (displayed in Table 8.6) to analyze data on whether a respondent voted for president in 2020. We update the by argument and refine the header. The resulting table is displayed in Table 8.7.

anes_des_gtsum5 <- anes_des %>%

drop_na(VotedPres2020) %>%

tbl_svysummary(

include = TrustGovernment,

statistic = list(all_categorical() ~ "{p} ({p.std.error})"),

missing = "no",

digits = list(TrustGovernment ~ style_percent),

label = list(TrustGovernment ~ "Trust in Government, 2020"),

by = VotedPres2020

) %>%

modify_footnote(update = everything() ~ NA) %>%

modify_header(

label = " ",

stat_1 = "Voted",

stat_2 = "Didn't vote"

) %>%

modify_spanning_header(all_stat_cols() ~ "% (s.e.)") %>%

as_gt() %>%

tab_header(

"American voter's trust

in the federal government by whether they voted

in the 2020 presidential election"

) %>%

tab_source_note(

md("*Source*: American National Election Studies, 2020")

) %>%

tab_footnote(

"Question text: How often can you trust the federal government

in Washington to do what is right?"

)| American voter's trust in the federal government by whether they voted in the 2020 presidential election | ||

| % (s.e.) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Voted | Didn’t vote | |

| Trust in Government, 2020 | ||

| Always | 1.1 (0.2) | 0.9 (0.9) |

| Most of the time | 13 (0.6) | 19 (5.3) |

| About half the time | 32 (0.8) | 30 (8.6) |

| Some of the time | 45 (0.8) | 45 (8.2) |

| Never | 9.1 (0.7) | 5.2 (2.2) |

| Source: American National Election Studies, 2020 | ||

| Question text: How often can you trust the federal government in Washington to do what is right? | ||

8.3.2 Charts and plots

Survey analysis can yield an abundance of printed summary statistics and models. Even with the most careful analysis, interpreting the results can be overwhelming. This is where charts and plots play a key role in our work. By transforming complex data into a visual representation, we can recognize patterns, relationships, and trends with greater ease.

R has numerous packages for creating compelling and insightful charts. In this section, we focus on {ggplot2}, a member of the {tidyverse} collection of packages. Known for its power and flexibility, {ggplot2} is an invaluable tool for creating a wide range of data visualizations (Wickham 2016).

The {ggplot2} package follows the “grammar of graphics,” a framework that incrementally adds layers of chart components. This approach allows us to customize visual elements such as scales, colors, labels, and annotations to enhance the clarity of our results. After creating the survey design object, we can modify it to include additional outcomes and calculate estimates for our desired data points. Below, we create a binary variable TrustGovernmentUsually, which is TRUE when TrustGovernment is “Always” or “Most of the time” and FALSE otherwise. Then, we calculate the percentage of people who usually trust the government based on their vote in the 2020 presidential election (VotedPres2020_selection). We remove the cases where people did not vote or did not indicate their choice.

anes_des_der <- anes_des %>%

mutate(TrustGovernmentUsually = case_when(

is.na(TrustGovernment) ~ NA,

TRUE ~ TrustGovernment %in% c("Always", "Most of the time")

)) %>%

drop_na(VotedPres2020_selection) %>%

group_by(VotedPres2020_selection) %>%

summarize(

pct_trust = survey_mean(

TrustGovernmentUsually,

na.rm = TRUE,

proportion = TRUE,

vartype = "ci"

),

.groups = "drop"

)

anes_des_der## # A tibble: 3 × 4

## VotedPres2020_selection pct_trust pct_trust_low pct_trust_upp

## <fct> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl>

## 1 Biden 0.123 0.109 0.140

## 2 Trump 0.178 0.161 0.198

## 3 Other 0.0681 0.0290 0.152

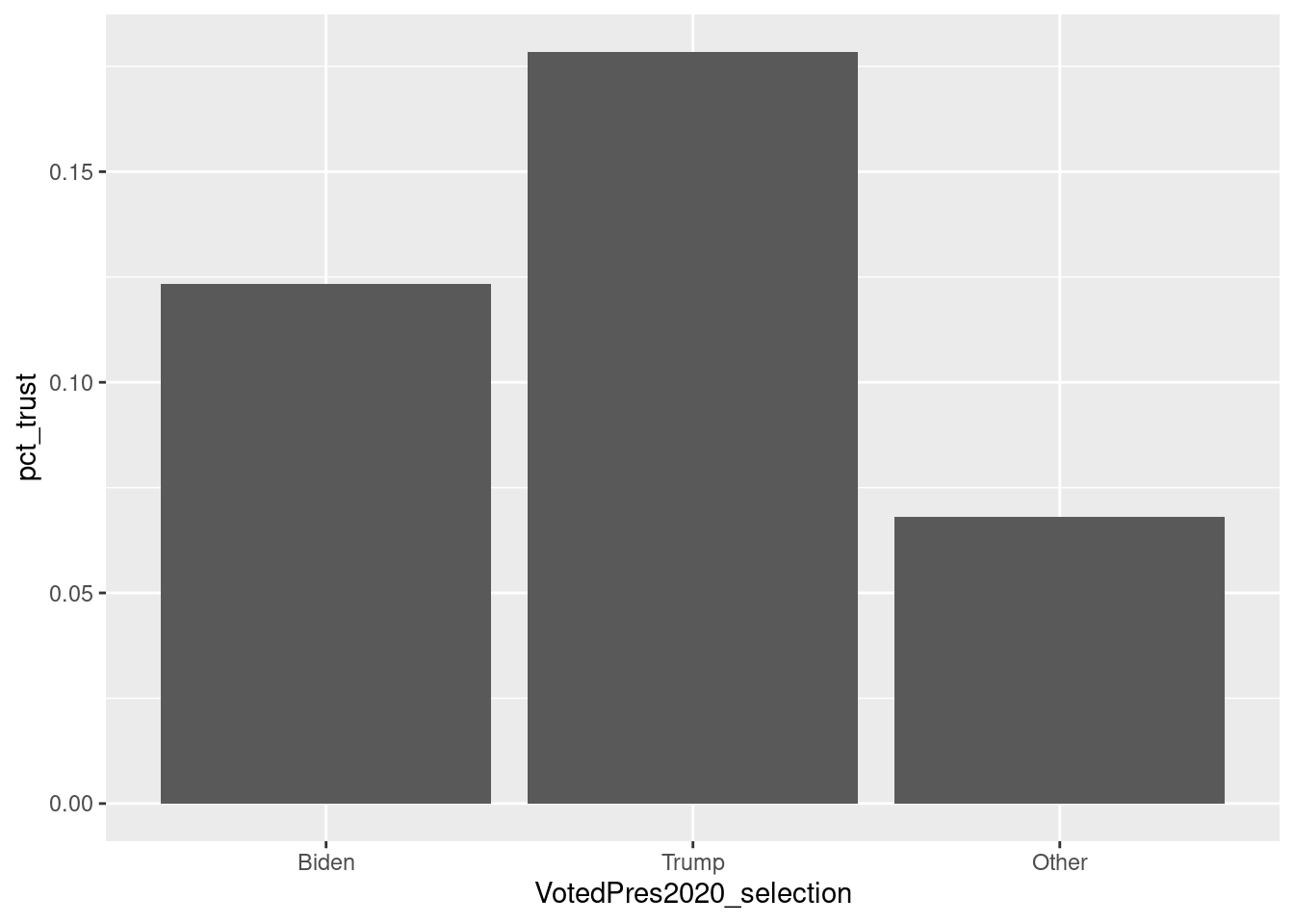

Now, we can begin creating our chart with {ggplot2}. First, we set up our plot with ggplot(). Next, we define the data points to be displayed using aesthetics, or aes. Aesthetics represent the visual properties of the objects in the plot. In the following example, we create a bar chart of the percentage of people who usually trust the government by who they voted for in the 2020 election. To do this, we want to have who they voted for on the x-axis (VotedPres2020_selection) and the percent they usually trust the government on the y-axis (pct_trust). We specify these variables in ggplot() and then indicate we want a bar chart with geom_bar(). The resulting plot is displayed in Figure 8.1.

p <- anes_des_der %>%

ggplot(aes(

x = VotedPres2020_selection,

y = pct_trust

)) +

geom_bar(stat = "identity")

p

FIGURE 8.1: Bar chart of trust in government, by chosen 2020 presidential candidate

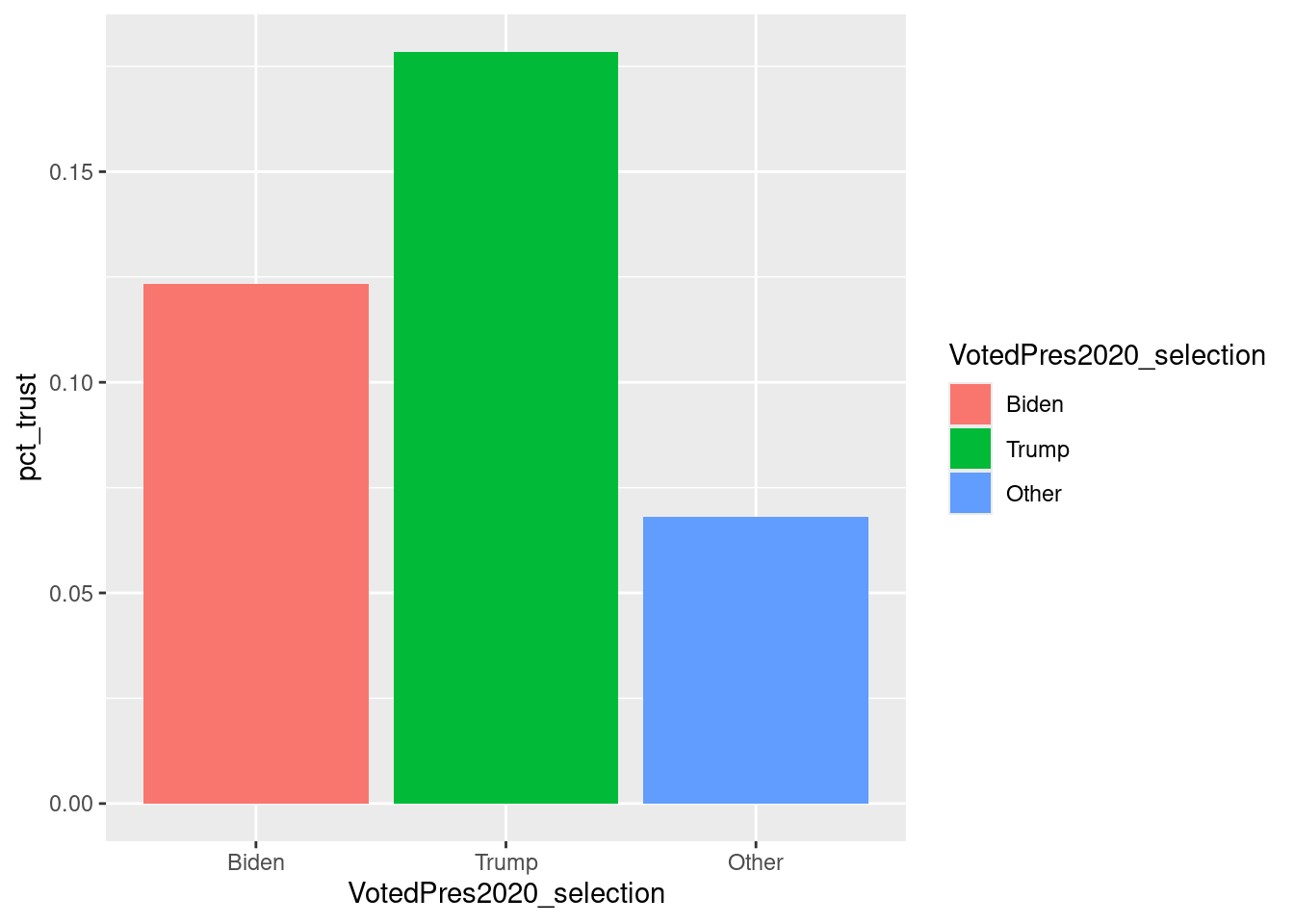

This is a great starting point: it appears that a higher percentage of people state they usually trust the government among those who voted for Trump compared to those who voted for Biden or other candidates. Now, what if we want to introduce color to better differentiate the three groups? We can add fill under aesthetics, indicating that we want to use distinct colors for each value of VotedPres2020_selection. In this instance, Biden and Trump are displayed in different colors in Figure 8.2.

pcolor <- anes_des_der %>%

ggplot(aes(

x = VotedPres2020_selection,

y = pct_trust,

fill = VotedPres2020_selection

)) +

geom_bar(stat = "identity")

pcolor

FIGURE 8.2: Bar chart of trust in government by chosen 2020 presidential candidate, with colors

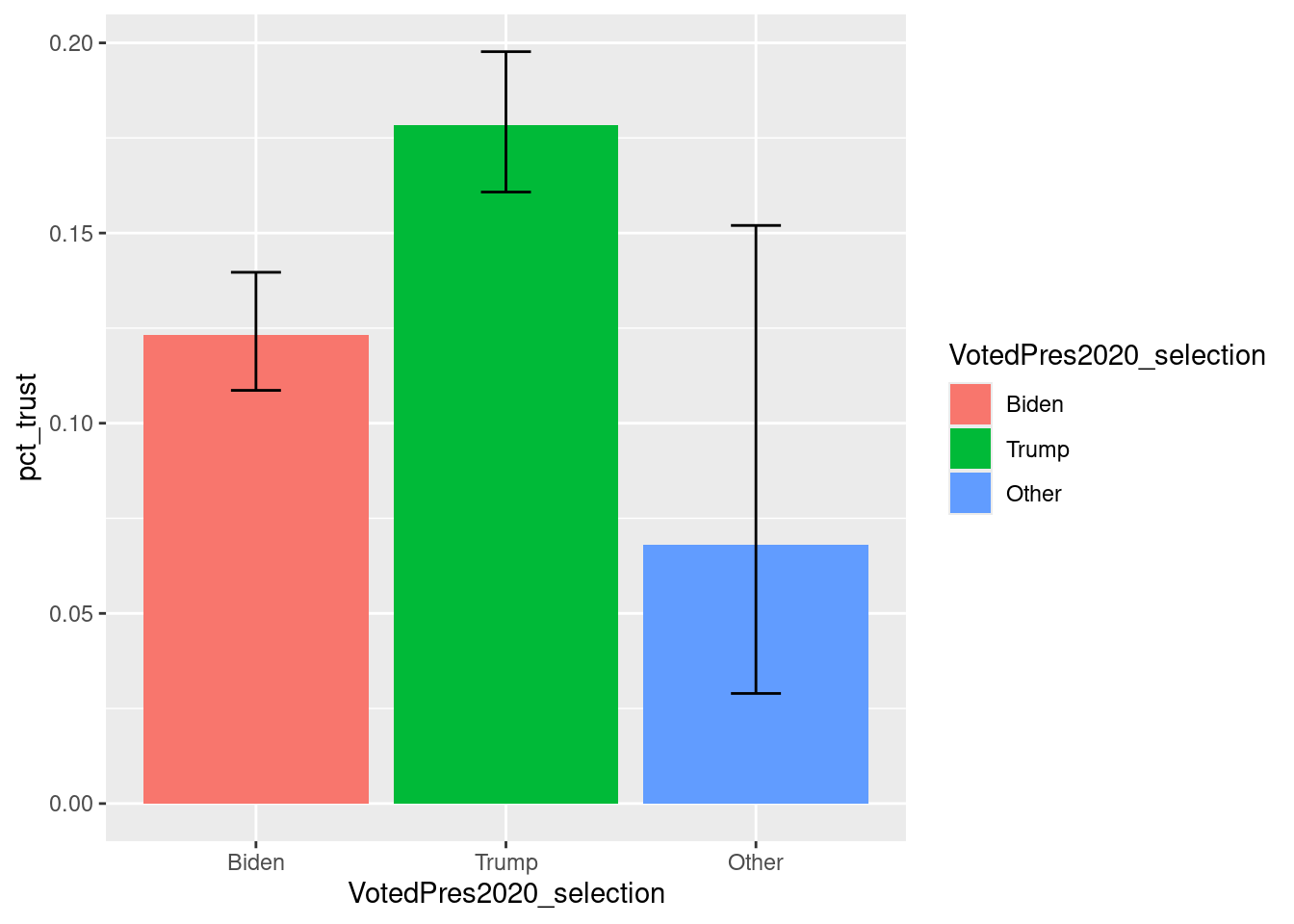

Let’s say we wanted to follow proper statistical analysis practice and incorporate variability in our plot. We can add another geom, geom_errorbar(), to display the confidence intervals on top of our existing geom_bar() layer. We can add the layer using a plus sign (+). The resulting graph is displayed in Figure 8.3.

pcol_error <- anes_des_der %>%

ggplot(aes(

x = VotedPres2020_selection,

y = pct_trust,

fill = VotedPres2020_selection

)) +

geom_bar(stat = "identity") +

geom_errorbar(

aes(

ymin = pct_trust_low,

ymax = pct_trust_upp

),

width = .2

)

pcol_error

FIGURE 8.3: Bar chart of trust in government by chosen 2020 presidential candidate, with colors and error bars

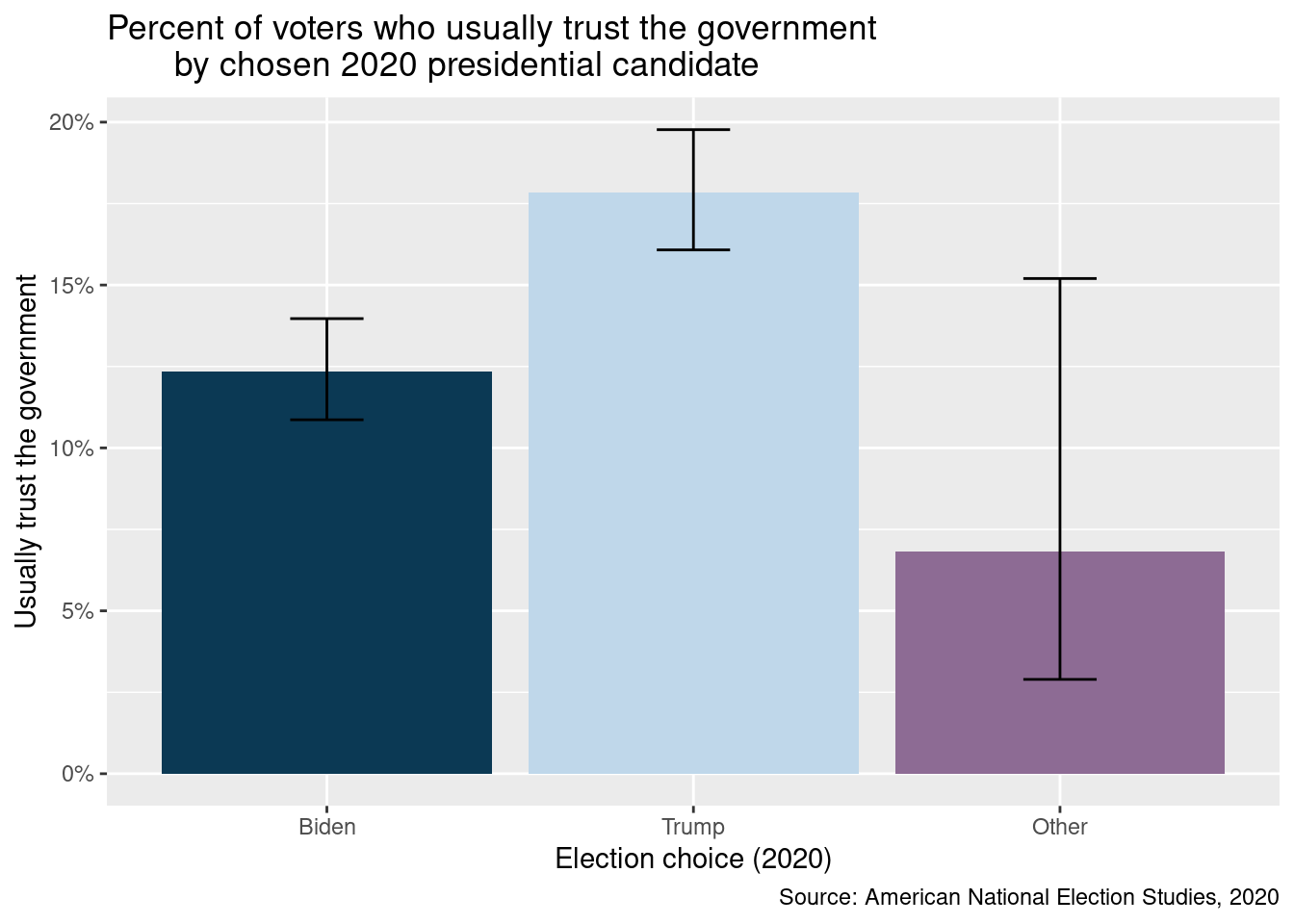

We can continue adding to our plot until we achieve our desired look. For example, since the color legend does not contribute meaningful information, we can eliminate it with guides(fill = "none"). We can also specify colors for fill using scale_fill_manual(). Inside this function, we provide a vector of values corresponding to the colors in our plot. These values are hexadecimal (hex) color codes, denoted by a leading pound sign # followed by six letters or numbers. The hex code #0b3954 used below is dark blue. There are many tools online that help pick hex codes, such as htmlcolorcodes.com. Additionally, Figure 8.4 incorporates better labels for the x and y axes (xlab(), ylab()), a title (labs(title=)), and a footnote with the data source (labs(caption=)).

pfull <-

anes_des_der %>%

ggplot(aes(

x = VotedPres2020_selection,

y = pct_trust,

fill = VotedPres2020_selection

)) +

geom_bar(stat = "identity") +

geom_errorbar(

aes(

ymin = pct_trust_low,

ymax = pct_trust_upp

),

width = .2

) +

scale_fill_manual(values = c("#0b3954", "#bfd7ea", "#8d6b94")) +

xlab("Election choice (2020)") +

ylab("Usually trust the government") +

scale_y_continuous(labels = scales::percent) +

guides(fill = "none") +

labs(

title = "Percent of voters who usually trust the government

by chosen 2020 presidential candidate",

caption = "Source: American National Election Studies, 2020"

)

pfull

FIGURE 8.4: Bar chart of trust in government by chosen 2020 presidential candidate with colors, labels, error bars, and title

What we have explored in this section are just the foundational aspects of {ggplot2}, and the capabilities of this package extend far beyond what we have covered. Advanced features such as annotation, faceting, and theming allow for more sophisticated and customized visualizations. The {ggplot2} book by Wickham (2016) is a comprehensive guide to learning more about this powerful tool.

References

The

tab_caption()function is intended for usage in R Markdown, Quarto, or bookdown to add cross-references across the document. The caption is placed within the table based on the output type. Thetab_header()function adds a title or subtitle to a table in any context, including Shiny or GitHub-flavored Markdown, without cross-referencing. The header is placed within the table object itself.↩︎